We’re in the midst of an exciting paradigm shift in the world of mobility.

Just a few years back, there were only a few methods of getting around cities, including bikes, personal vehicles and public transportation. Today getting from A to B is increasingly personalized. Building on traditional transportation options, now on-demand ride hailing, innovative car subscription services and free-floating micromobility offers are becoming commonplace. All of these new mobility offerings have sparked the rise of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS). If you’re not yet familiar with MaaS, here’s a good article to check out.

MaaS has become a trendy buzzword over the past few years, mainly due to its great potential to reduce car ownership and make urban transportation more sustainable. But looking beyond the hype, what are the assumptions and misconceptions about MaaS? Where can it add value?

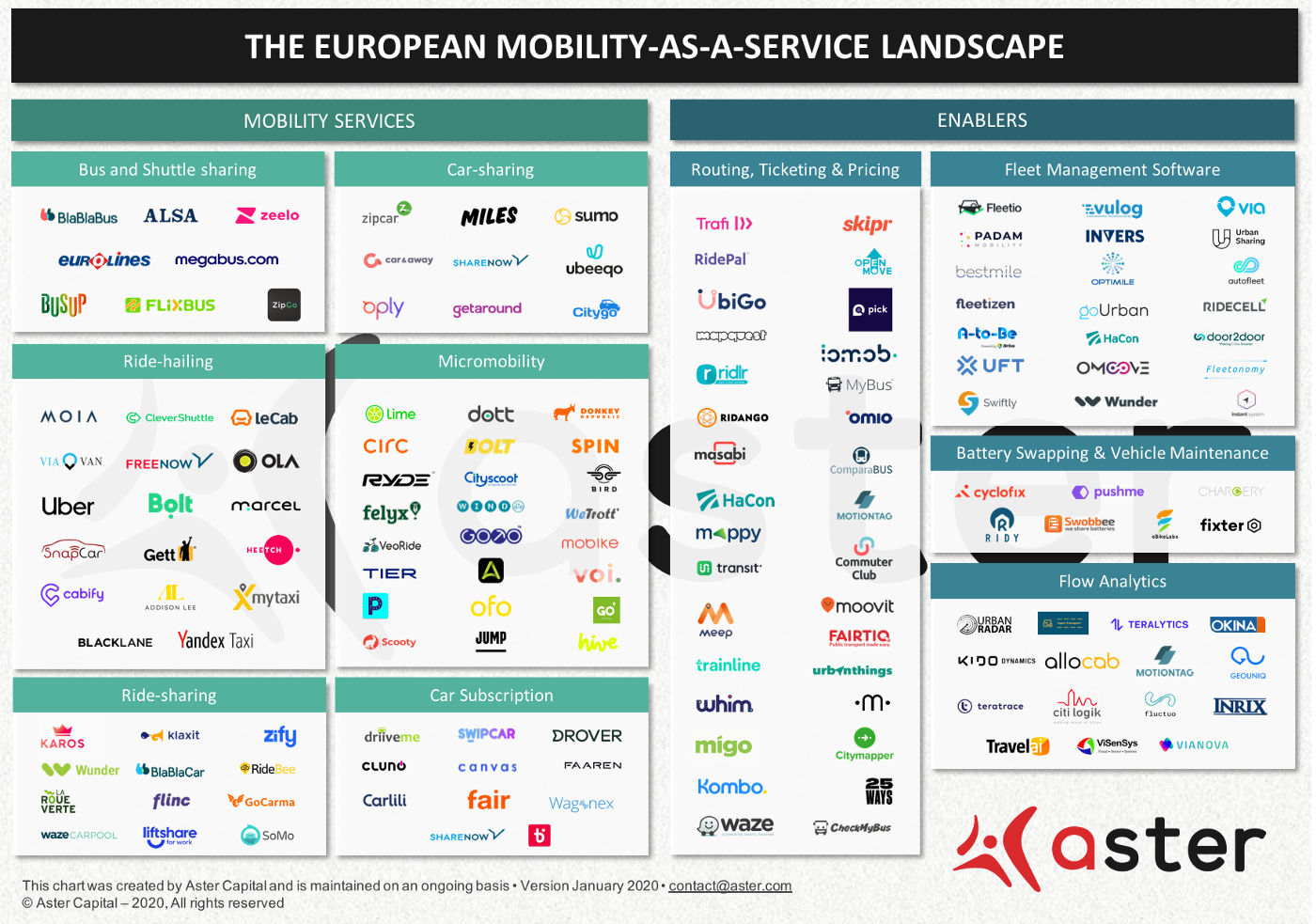

Mobility being one of the areas we are passionate about here at Aster, we’ve studied up on the subject and want to share our take on four of the most common MaaS myths that we’ve come across.

Myth #1: Blitzscaling is a recipe for success in the world of MaaS

Investors have poured money into new modes of transportation in recent years, encouraging ride-hailing, e-bike and e-scooter startups to leverage a “Blitzscaling” approach, where speed is prioritized over efficiency in uncertain environments. Indeed, this strategy makes sense in a market where there is little to no brand awareness, network effect or even economies of scale. It’s about who raises the largest amount of money to be able to flood the market fast and kill out competition. And in times of large capital availability and Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), investors are often keen on backing up these models.

But blitzscaling has had some pitfalls in the MaaS market, where it has so far turned out to be more effective for burning cash than increasing market share.

In the ride-hailing market, Uber and Lyft have been spending massive amounts of money to compete over a few points of market share. According to Agence15marches, Uber at one point dedicated 55% of their revenue on promotions and other benefits, while Lyft spent up to 127% of its revenue on marketing prior to IPO. Even though private investors trusted Uber with $24.7 billion worth of equity and debt, its unsustainable business model is one of the main reasons the company saw its public valuation fall from an expected $120 billion to $82 billion on its IPO to $56.47 billion as of today (28/10/2019).

The downsides of blitzscaling can be also be seen in the micromobility segment. After raising $2.2 billion and flooding cities across the globe with bikes, Alibaba-backed Ofo backpedaled from international markets and is now fighting for survival as it struggles to pay back debts to users and suppliers. Ofo’s competitor Mobike has a similar story, announcing in March of this year it would be cutting operations from most international markets. This is without mentioning the negative externalities of such an approach.

Myth #2: The e-scooter is the cash cow of micromobility

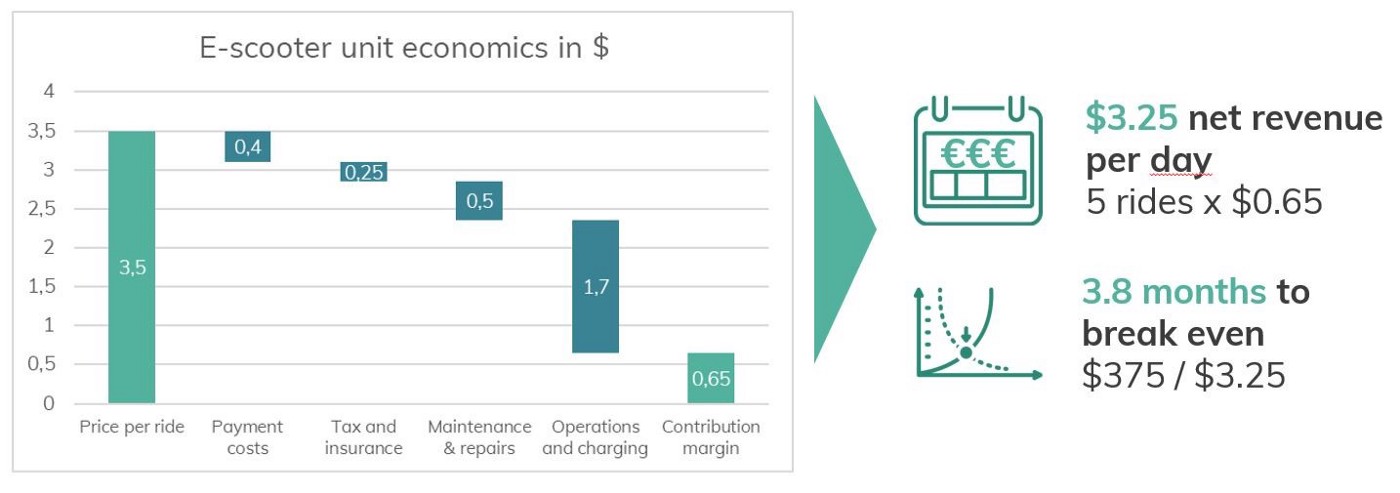

The e-scooter has strong pricing ratios between CapEx + OpEx compared to its bike, e-bike and e-moped counterparts. That’s why it is often perceived as the sweet spot of the free-floating mobility world. And yet, when digging into the unit economics of the first generations of e-scooters, we can begin to understand why operators are struggling to cut the fierce cash burn.

The breakeven for e-scooters takes almost 4 months, and with hardware durability issues and vandalism, operators are unprofitable in many cities. While we expect new generations of e-scooters to have longer lifetimes, we’ve seen that these issues remain as some of the key hurdles that makes current e-scooters uneconomical.

The first generations of e-scooters have struggled in reaching profitability

That said, adoption has been impressive, and we believe e-scooters are here to stay. Cutting operational costs will be crucial, so we expect companies in the space to adopt new approaches towards charging, such as battery swapping (which we’ve been looking at closely) and maintenance. But to win in the market, companies will need to become very hardware oriented to improve bottom lines (several players, including Skip and Lime, have already brought the design of their recent e-scooters in-house).

So far, the e-scooter is not the cash cow that everyone was expecting and has become more of a hardware play, as operators are now refocusing their efforts on vehicle design and manufacturing.

Myth #3: Transportation is about to become “Spotified”

No one would be talking about MaaS without routing, ticketing and pricing applications to take people from A to B in a smooth and multi-modal way. Capturing value on the value chain is not an easy game since margins are already quite low, so MaaS applications are trying to find innovative business models, such as subscription-based mobility packages.

MaaS companies offering these mobility packages are often viewed as the “Spotify of Transportation”. These players are ultimately trying to create a future where people can travel in urban areas without a car by bundling several public and private transport offerings together in the most convenient way possible.

But can MaaS players be compared to Spotify and Netflix? To answer this question, we’ve compared the spread of the marginal costs and gross margins between Spotify and Whim. Spotify’s premium service is priced at $9.99, and has an average per stream payout to rights holders of between $0.006-$0.0084. The company has also been producing its own content in order to increase gross margins. This can hardly be compared to the costs a 30-minute bike ride or a 5km taxi ride, which are priced at €1 and €10 by Whim, respectively. Plus, keeping control over the gross margin is much harder in MaaS, as customers subscribing to an unlimited mobility package are more inclined to use taxis and ride-sharing than bikes or public transit.

Myth #4: Transportation is now a private player playground

City control over urban transport has been shaken with the arrival of new mobility services. When looking at the MaaS landscape, we see many private companies, and most mobility services in cities are now operated by private players. So is there still space for cities and public players in the urban mobility market, and if so, what role do they have?

Some recent examples show the market still remains somewhat regulated: Lime and Bird launched their fleets across 43 markets in the US without government permits or consent, but in quite a few cases have faced fines or even cease and desist orders. Waze was blamed for turning quiet residential areas into urban highways — but cities were able to add traffic lights or fake traffic jams to limit the flow.

The rise of MaaS shouldn’t hurt public transportation, which today remains on the podium for its excellent ratio between speed, the number of riders and environmental impact. In fact, global mass transit ridership has grown from 45.5 billion in 2012 to 53.77 billion in 2017. Instead, we believe that MaaS can complement existing transport offerings.

In the end, cities need MaaS, and MaaS needs cities.

MaaS offers a variety of benefits for cities, as it enhances existing transport offerings, reduces congestion and pollution, optimizes infrastructure investments and expands transport inclusivity for underserved inhabitants. On the other hand, MaaS players depend on cities to expand into new markets and integrate into public infrastructure. Moreover, cities can also provide incentives and subsidies to certain MaaS providers to encourage more sustainable transportation.

A handful of public actors are already taking proactive and collaborative approaches towards MaaS:

– Incentivizing: Île-de-France Mobilités decided to provide monthly subsidies to the carpooling drivers and passengers of innovative mobility players such as Karos in April 2019, with the aim of reducing congestion and pollution.

– Experimenting: Portland created the “E-Scooter Pilot Program” in 2018, designed to assess whether scooters operators can help meet the city’s transportation needs.

– Integrating: BVG (Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe) launched the “Jelbi” app in Berlin with the help of a white label solution powered by Trafi, a mobility tech platform provider, enabling commuters to seamlessly plan and book trips with public and private mobility services on one app. Louisville’s Transit Authority of River City (TARC) created a similar app in May 2019, also letting commuters book multi-modal trips with public and private modes of transportation.

Conclusion

So there you have it, four different MaaS myths debunked!

But what opportunities lie ahead in MaaS? In our next article, we will share some insights on this question and highlight some of the ways that MaaS players can help their customers add new revenue streams, cut costs and gain a competitive edge.

As a bonus, we would like to share our landscape of the different players operating in the MaaS world, which we’ll be updating as the market evolves: