The Grid is becoming smarter, but is that enough for incumbent energy operators and utilities to meet the new challenges they are facing?

Smart grids are energy networks that can automatically monitor energy flows and adjust to changes in energy supply and demand accordingly. We all see nowadays a wide-spread use of the words “smart grid” or “edge grid”, also outside the energy community strictly speaking. Also, huge investments are expected: analysts and think tanks are debating about the latest projections — recent World Economic Forum report speaks about $2.4 trillion value created by innovation in the electricity industry over the next decade. So how did we get to that point?

Solar and Wind

About 10 years ago, the cost of electricity generated by sun rays hitting polysilicon crystals was approximately $500/MWh. Today the same electricity costs about $50/MWh (and in some cases less[1]), and the cost of wind energy has followed a similar path. The sharp reduction in the cost of the renewable generation has strengthened its position as a credible alternative to traditional sources (especially gas and coal). Even after the end of generous incentives programs, the result today is that most of the new installed capacity, at least in developed countries, is Renewable (see this nice article about “solar singularity” by Greentech Media).

That wouldn’t impact the grid that much, if not for one main reason: intermittency. Solar and Wind are not “dispatching sources”, or in other words are not “programmable”: you cannot say to the Sun <<shine!>> and to the Wind <<blow!>>. The immediate result of that intermittency is that the electricity grid now doesn’t know in advance where the energy will be produced, or how much, and that’s an enormous challenge for grid operators.

Distribution of energy generation

Not only energy generation has become cheaper through renewables, but it has also become increasingly distributed on a scale that never existed before. Now, in some countries, the electricity needed to run a washing machine or watch TV can be produced on your roof at the same cost (or cheaper in some cases) than the electricity you can buy from the grid.

While this is convenient for the clients it adds a second challenge for the grid and the operators: we are moving from a network structured around centralized production plants to a network of many disparate sources.

Energy storage

Historically, there has not been any obvious ways to accumulate energy produced. As a result, massive quantity of renewable electricity enters the grid, outnumbering the demand (especially at night, when wind blows the most and the demand is the lowest). As the value of electricity is typically set by tradeoff between demand and supply, negative prices are being observed with increasing frequency, or energy is exported from countries with excess of renewable production (Germany for instance) at very cheap prices. Fortunately, also thanks to the massive volume expected from automotive applications, Li-ion batteries are now less than $230/kWh (McKinsey study, 2017[2]) compared to $1000/kWh 5 years ago. Now renewable asset owners have increasingly the choice of trading the electricity they produce (i.e. deciding whether to store, consume or sell), again adding another challenge to grid operators and incumbents: the energy produced will not necessarily be entering the grid immediately as we have the option to store it within batteries.

Major new dynamics such as A/ affordable renewable generation, increasingly distributed on a large scale, B/new energy exchanges and trading opportunities, C/ hard time to predict demand and offer and their topography, are creating massive challenges to incumbents. Is the “smart grid” enough to cope with all that?

Smart meters were only the start

Historically, utilities have generated and monitored quite some data from their production assets, the substations at both low and mid/high voltage level, and to some extent at the point of consumption. But now, many scattered production assets belong to customers, and monitoring only traditional assets is not enough. Hence why, for a few years now, utilities have seen the interest to deploy “smart” meters to learn more about customers’ behavior, both from demand and production points of view.

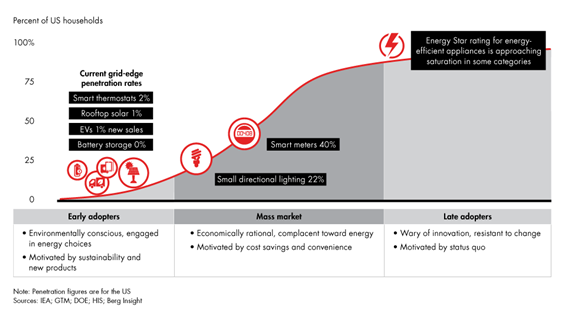

While smart meters are considered entering the mass market (see chart above) many more connected devices are beginning to be deployed by early adopters. The new devices are no longer limited to consumption-related devices, with rooftop solar and behind-the-meter battery storage both generating “production” related data. Information is increasingly more accessible and transparent to any player, even outside the traditional energy value chain, including end users and consumers.

Utilities are finally learning that it is not just about being able to deploy and read smart meters. In fact, the complexity that has stacked up on the energy ecosystem is far greater to be dealt with only with smart meters.

Utilities are expected to respond with massive IoT and data-related investments

In 2017, IDC predicts[3] that utility investments into smart grid technologies will represent $56Bn of the $66Bn IoT investments they are expected to make this year. Three major use cases are likely to drive such investments[4]: smart meters, distributed generation and demand response. The investments will be mostly directed at solving short term pain points utilities are facing and will try to leverage as much as possible the data generated.

Having said that, many difficult questions remain: who is to finance the capital investments needed to maintain and upgrade the grid now that the value of the energy in transit is decreasing? What is the right balance between operational cost savings, system stability and reliability on the one hand, and revenue and margin improvement on the other hand?

One thing however is clear: whoever doesn’t take advantage of the massive data generated will be left behind. A 2016 Bain & Co study suggested a doubling or tripling the average number of variables taken into consideration to build a model predicting power outages, for instance, will improve the accuracy of events predicted by 2–3X. In turn, this will reduce the cost and the negative impact on customers from dealing with such outages by an equivalent proportion. If you consider more data in dealing with your business problems, you will have a quantifiable positive impact on your ROI. And the smarter you are about getting value out of data, the higher will be your ROI.

Troubles ahead for incumbents and role of innovative startup companies

As massive new investments from utilities and incumbents are focusing on deploying sensors (including smart meters) everywhere and supporting renewable generation capacity, we see a fundamental flaw in this approach: it doesn’t consider the customers’ needs as the main focus.

Failing to address customer centricity could be life threatening for utilities and incumbent players in the future. On the one hand, they enjoy increasing limited barrier at the entry and on the other hand, customers have a deeper awareness about the choices they have. To understand customers’ needs better, utilities and incumbent operators must master data analytics and switch their approach from looking inward to outward. This is no small task, but the good news is that many startups can offer inspiration.

Inspiring startups

Startup companies are disrupting the entire energy value chain. Some are taking advantage of new revenue streams available from flexibility options[5], such as KiwiPower, UpsideEnergy in the UK, or Restore in Belgium. Others are playing a pivotal role to build a new form of “collaborative” or “social” utility such as Sonnen or Lumenaza in Germany where individuals are exchanging the energy produced by their local distributed energy asset (solar PV especially). Finally, “independent energy retailers” are focusing on serving the final customer. Examples include FirstUtility in the UK, Lichtblick in Germany, or DirectEnergie and Ekwateur (an Aster portfolio company) in France. These companies are experiencing dramatic growth and are beginning to have a visible impact on major utilities’ market shares and, in turn, their P&Ls.

However, startup companies are also supporting incumbents to become smarter “customer oriented” players. Some are focusing purely on making data available, for instance to make it simple for utilities to publish data. This can include making it available through APIs as well as building applications which leverage the data. One such company in Aster’s portfolio is Opendatasoft. Others like Germany-based Thermondo are revolutionizing the sales process based on pure automation and data driven insights. They are currently focused on heating systems but plan to add solar PV soon, Other startups, such as Enbala in the US , Greencom Networks and Younicos (recently sold to Aggreko for $52m) in Germany, are positioned as providers of solutions that help utilities to tap into new revenues opportunities generate by an optimized electricity grid (Transactive Energy paradigm[6]).

Conclusion

We predict challenging times for incumbent players for the foreseeable future. However, some are learning the hard way and are taking action sooner through investing or partnering directly or indirectly with startups.

In the future, markets will be far more open and liberalized, the cost of producing electricity from renewables could possibly approach zero, and the value of existing traditional assets will need to be mostly written off. The survivors, whether incumbents or new entrants, will be the ones that master customer relationships and deliver valuable services through a deep understanding of customer’s needs. This will go mostly through mastering data collection and analytics.

In the meantime, the smart grid must serve new needs. The role of delivering high power to energy intense industries, integrating new utility-scale distributed generation facilities, and as well as complementing self-consumption for commercial and especially residential users will all need to be accomplished simultaneously.

[1] https://www.lazard.com/perspective/levelized-cost-of-energy-analysis-100/

[2] This is in fact an average, as stationary batteries tend to be more expensive (in the range of 300$/kWh) while mobile application batteries are in general cheaper (around $150/kWh) : http://www.mckinsey.com/global-themes/digital-disruption/harnessing-automation-for-a-future-that-works

[4] IDC, Gartner, BCG; data are from 2016.

[5] Demand Side Management, Demand Response.

[6] http://www.gridwiseac.org/pdfs/te_framework_report_pnnl-22946.pdf