There is a long, long list of companies offering on-demand services in a specific sector to replicate the success of Uber: from Instacart (grocery shopping) and UpCounsel (legal advice) to Wag-Walking (dog-walking) or Mowdo (lawn-mowing). But is the trendy business model of Uber really applicable in any industry?

Given the meteoric growth that companies like Uber, Lyft and a host of other competitors that match human passengers with drivers willing to escort them around cities, it has been posited that similar applications can be developed in the logistics industry. Uber itself announced an Uber Freight application a couple of weeks ago. The narrative goes that a service matching companies which need to ship a pallet or container of goods (instead of human passengers) with shipping carriers (instead of drivers using personal automobiles) provides an obvious opportunity for the business model which has seen such wide adoption in the passenger transportation market. That belief is often supported by drawing similarities between several criteria that have contributed to Uber’s success, including:

- A large market: the road logistics market is at least 6 times larger than the taxi market (in Europe, more than €300bn vs less than €50bn)

- Fragmentation on both sides of the platform: the average carrier company in Europe or in the US owns 3 trucks, and the number of companies that use freight services at least one time a year is huge.

- An inefficient market: the load factor in the logistics sector (the average load of trucks / capacity) is lower than 70%. Launching an UberPool service for trucks is one way to solve that.

- A global problem/opportunity. And a growing problem, as the road logistics industry is expected to triple by 2050, especially driven by the growth in emerging markets who face a lack of sea/air/rail infrastructure.

However, is it realistic to imagine an on-demand service where a community of carriers effectively competes with existing logistics companies?

Despite the optimism expressed in the perspective above, there are a number of reasons to believe that the opportunity in the logistics sector is smaller than many perceive. Those include:

- While the taxi prices are regulated, prices in the trucking industry are not. It’s actually the contrary, as prices vary a lot, depending on the size on the shipper, the time of transport, the line, the direction of shipping… It is difficult to act as an intermediary who would predict prices or provide instant pricing like Uber does, without large volumes and secured agreements with large carriers.

- For B2B companies, an instant service at the best price is not the primary driver. The primary driver is to be able to plan the delivery of goods at a defined price, and to be sure that the goods will safely arrive on time. I can wait for an Uber, but an industrial company cannot stop the production line because the missing parts were waiting for the end of the surge-pricing period before being shipped to maintain margins.

- As recently confirmed by the founders of Palleter (a European Uber for trucks) in an insightful Medium post, truck drivers’ priority is to deliver goods on-time, not to increase capacity factors. It makes sense at the system level for drivers to pick up extra loads to generate extra revenues, but few drivers really want to do so because the risk of disturbing their operations (e.g. delaying delivery, requiring repacking of the truck) is higher than the reward.

That’s why we believe that competing head to head with freight forwarders will be a daunting challenge for new entrants.

Don’t get us wrong: there IS opportunity for “Uber for trucking” startups

Many companies have raised money with the ambition to become the Uber for trucks, and we have no doubt that there will be some very large successes. We have met and been impressed by the teams at Convargo, Chronotruck, Ontruck and other great firms recently. The frictionless model with instant quoting is particularly useful for small and medium businesses who are not regular users of road logistics services. It could be useful for large companies to do shipments out of the “baseload” negotiated with freight forwarders.

How technology will affect the logistics value chain

Just because the Uber model does not look applicable to the logistics sector does not mean that new technologies will not impact the logistics sector. The logistics value chain is likely to remain intact, but each link of the value chain will benefit from different innovations.

On one side of the value chain, the day-to-day decision making of the shippers is mainly driven by two factors. First, do I get the best price to ship my goods? Second, will my goods arrive on time, and without any problem? The level of uncertainty will be drastically reduced with long-lasting trackers that can accurately and continuously monitor location, temperature or vibration of goods. Startups focused on tracking solutions include Traxens at the container level, Palletech at the pallet level, or Kizy Tracking at the parcel level. Some companies focus on the data aggregation from different transport parties to provide a unified view of the shipments to the shippers (like Shippeo). Shippers have also the opportunity to share the quotes they get and the price they pay for different routes with a crowdsourced price comparison service (like Xeneta, for ocean freight only).

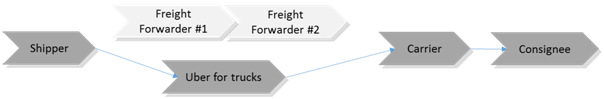

On the other side, the freight-forwarders, who are the intermediaries between the carriers and the shippers, want to automate their operations workflow (quoting, transaction, tracking, settlement) as much as possible. Despite the fact that the quoting process is likely to require direct negotiation with the customer, a data-driven sales solution would at least help their sales team negotiating with a clearer picture of the margins (like the solution of Freightos).

These are a few examples to illustrate that the transformation in the logistics industry aims primarily at reducing the friction between the different actors. And if there is one company whose strategy related to logistics embodies this principle, this is Amazon.

Who is leading the transformation in logistics?

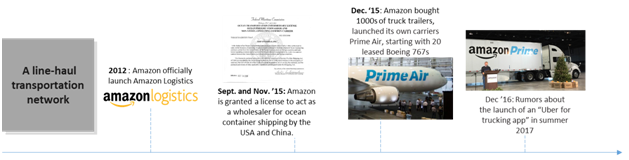

Amazon appears to be one of the players leading the transformation in the industry. By amassing inventory from thousands of merchants, Amazon started by securing the volume to buy space on trucks, planes and ships at reduced rates. But their strategy changed in 2015, when the company took advantage of its financial power to build its own integrated long-haul transportation system. The IT and data expertise of Amazon is a key asset to achieve their vision of “a revolutionary system that will automate the entire international supply chain and eliminate much of the legacy waste associated with document handling and freight booking.” Amazon’s ambitions are likely to inspire start-up founders and large corporations alike to rethink the status quo.